TIFs (Tax Increment Financing) have received a ton of coverage in the news recently because of the recent debates about two of Chicago’s largest ever planned real estate development projects: Lincoln Yards and The 78. These two developments will benefit from up to $2.4 B in TIF money, which has been one of the more controversial aspects of these developments. In fact, two activist groups filed a lawsuit last week alleging that the approved TIF for Lincoln Yards violates Illinois law.

TIFs started in California in 1952 and have since been used throughout all 50 states. They have also been a popular public financing technique in Chicago. In fact, if you look at all the TIF “districts” in Chicago mapped out you’ll see that a huge portion of the city is covered by them. Check out the small map at the top of this post and click on the link in the previous sentence for a more detailed view. One thing to note, though, is that their definition of a TIF district is pretty liberal. So a huge portion of the city is defined as a district just because of planned L modernization.

As I’ve monitored the news and discussions around Chicago TIFs I’ve discovered that there is a awful lot of misunderstanding out there about exactly how these things work. You’ll see it in the way people talk about them. So I decided to spend a little bit of time addressing some of the more basic concepts and associated misunderstandings. They’re not quite as bad as some people believe.

TIFs Do Not Take Tax Dollars Away From Other Programs

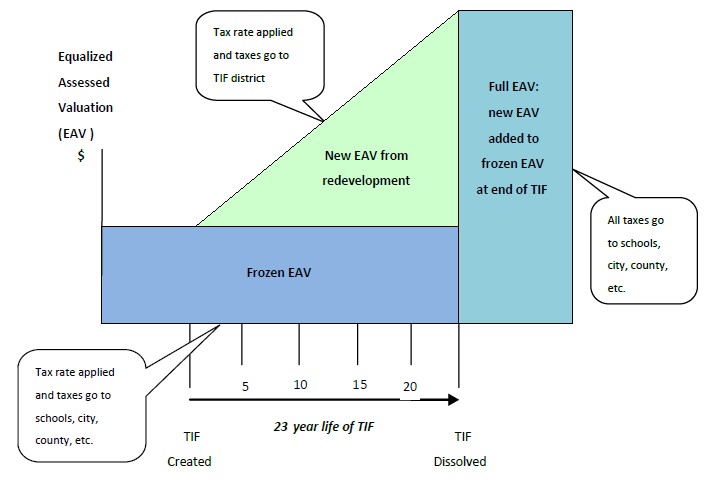

You will often hear people claim that TIFs are depriving communities or schools or other projects from much needed tax dollars. Or that property taxes in a TIF district will be frozen for 23 years. Neither of those claims are exactly correct. The way TIFs work is that the original tax dollars from the original tax base are still available to the general revenue fund but incremental tax dollars are collected from the improved tax base and go towards paying for infrastructure – for 23 years. After that all tax dollars go to the general fund. There is a ubiquitous, yet often ignored, diagram that helps illustrate this basic financial structure.

So, the city/ county continue to collect all the taxes they were already collecting. However, an argument can be made that 1) the development increases the demand for other city services that are not beneficiaries of the TIF funds and 2) the city does not benefit from the increase in the the original tax base that would have occurred had the development not proceeded.

Where Does TIF Money Go?

According to the Illinois Tax Increment Association, in principle, TIF money is supposed to go towards:

- Property acquisition

- Rehabilitation or renovation of existing public or private buildings

- Construction of public works or improvements

- Job retraining programs

- Relocation

- Financing costs, including interest assistance

- Studies, survey and plans

- Professional services such as architectural, engineering, legal, property marketing and financial planning

- Demolition and site preparation

- Day care services

So I think this is where a lot of the backlash to TIFs comes from. A lot of these authorized uses of the money are costs that developers normally pay for themselves. So, in essence, the money can become a de facto subsidy to the developer. It all depends on how good the city is in negotiating the terms.

Originally, the impetus for TIF funding was to incentivize development in “blighted” areas. And the need for the incentive was to be determined by applying the “but for test” – i.e. the development would not occur but for the TIF funding. According to the Illinois Tax Increment Association Illinois 1) the evidence that the development passes the test is supposed to be included in the Redevelopment Plan and 2) Illinois has the toughest but for test in the nation.

So, if the city determines that the development passes the test and the area is seriously blighted then they may choose to bestow lavish subsidies on the developer through the TIF program. It depends on the development.

However, the math is a bit suspicious. Are we to believe that the absolute minimum TIF money needed for a project is ALWAYS EXACTLY equal to 23 years worth of incremental property tax dollars? The Association indicates that many TIFs (30 since 1977) were voluntarily terminated early but they provide no indication of what percentage of the total that is and it sounds like the TIFs are always set up for 23 years.

No Doubt TIF Accounting Is Opaque

I think this is another area where there is a huge problem that needs to be fixed if the city would like the public to support this mechanism. It’s really hard to find out how the TIF money is spent. I’ve looked around for it and can’t find it. If you know where it is for even one project let me know in the comment sections below.

Unfortunately, investigations have turned up evidence in the past that money has been diverted from TIF funds to projects that were not the original intended beneficiaries of the programs. That doesn’t help the credibility of the program.

*************************

If you think I’ve left out an important point or if you disagree with anything I’ve written please respond in the comments below. I may revise my post accordingly.

Although my next post will be about the Case Shiller home price index I intend to return to this subject soon after that by taking a closer look at the TIF for the Lincoln Yards project.

#TIFs #TaxIncrementFinancing

Gary Lucido is the President of Lucid Realty, the Chicago area’s full service real estate brokerage that offers home buyer rebates and discount commissions. If you want to keep up to date on the Chicago real estate market or get an insider’s view of the seamy underbelly of the real estate industry you can Subscribe to Getting Real by Email using the form below. Please be sure to verify your email address when you receive the verification notice.