If you look at enough Chicago Public school report cards you will start to notice a pattern in the test scores. It looks like schools with a lower percentage of low income students tend to have higher test scores – or, more precisely, a higher percentage of students that meet or exceed the standards. That may not be a surprise to many people. However, it’s one thing to think you see a pattern and another thing to actually get your hands on the data and then see a real pattern. So I’ve always wanted to do a scatter analysis of the Chicago Public Schools’ test scores data to confirm the pattern but assumed that it would be a lot of work to pull the data. Then the data fell in my lap.

Let me first side step for a minute here and explain that I am by no means claiming that test scores are the end all/ be all for determining the quality of a school. However, I will tell you that parents who are deciding where to buy a home are absolutely looking at test scores or, even worse, looking at one of those composite ratings out there that attempt to boil down a school’s “quality” into a single number, which you know is based at least partly on test scores. And as you will see in a minute you need a really large dose of perspective in order to even begin to understand what’s behind these test scores.

So it turns out that the state of Illinois actually makes this data readily available in exactly the way I was hoping to see it – a series of scatter diagrams that compare Chicago Public Schools’ test scores to different readily available variables. The only problem is that you might never find it on your own. It’s buried in some obscure section of some obscure Web site. I totally stumbled on it with a little help from the Illinois State Board Of Education.

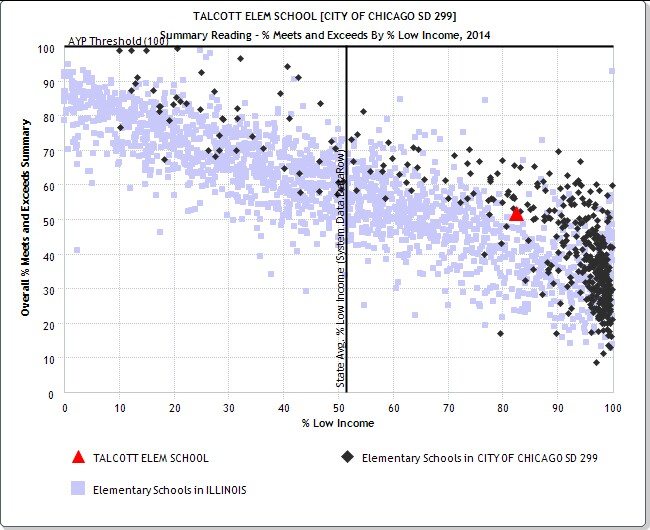

I think the only way to get to the diagrams is by picking a particular school for comparison purposes. The sample data I am using below just happens to be pulled from the Illinois Interactive Report Card for Talcott, which is in my East Village neighborhood. The report just happens to default to income, and sure enough there is a clear pattern: fewer low income kids means more kids meeting or exceeding the test score standards.

But several other interesting patterns come out of the data. First, there is a great deal of variation in test scores around any given % low income. In other words, the percentage low income students does not explain 100% of the variation in test scores. Duh! But what that also means is that maybe you should be more impressed with the “quality” of McDade that has 94% meets or exceeds with 41% low income students than with the “quality” of Bell that has 89% meets or exceeds with only 13% low income students. I don’t know any of the detailed circumstances surrounding these two schools but I’m just saying…BTW, the graph shows Talcott as the red triangle and it’s at the lower end of the range for it’s low income percentage.

Second, you should notice that, in general, for any given % low income the Chicago Public Schools tend to do better than the overall population of Illinois schools. That’s pretty interesting, isn’t it?

So let’s think about this some more. People talk about a school “improving” over time. How does that actually happen? Doesn’t this usually happen in higher income neighborhoods? And isn’t it accompanied by more higher income parents sending their kids to the school? A few parents send their kids there. Test scores go up. More parents send their kids there…Get the picture? It’s called a positive feedback loop.

But has the school really improved? I guess it’s possible. Maybe the parents really do make some kind of change in the school that benefits all the kids. Is there any data to support this? And if it were true would you expect the improvements made to somehow be proportional to the percentage of low income students – i.e. the more affluent kids that go to a school the more “improvements” the school makes? That doesn’t sound plausible to me.

But wait, there’s more! Notice that, above the graph, there is a drop down where you can select other student groups – i.e. different variables for the x axis. Among others, some of the more interesting variables are attendance rate and mobility (kids switching schools), both of which also appear to be highly correlated to test scores. Now, this is an excellent opportunity for us to step aside again for a minute so that we can all review statistics 101. CORRELATION DOES NOT IMPLY CAUSATION. This seems to be a concept that is totally forgotten in 99% of the conversations that take place in social media. I think this should be one of the questions on the ISAT if it’s not there already.

What’s my point? My point is that it’s very tempting to look at this data and conclude that we know what causes low test scores. Well, maybe. Maybe not. You can’t really know because all you have is a correlation. And you have correlation with 3 different variables, all of which I am sure are correlated with each other – e.g. lower income families probably move a lot and that creates higher mobility of the students. And if one variable drives another variable then maybe you can argue that the driving variable is the real cause. Or maybe not. Maybe there is some other exogenous variable that is driving everything. We don’t really know.

Maybe you would know if you could actually describe the mechanism by which one thing leads to another. For example, and I’m not a social scientist so I’m just making this up, lower income families tend to rent so they tend to move a lot so their kids end up switching schools and they end up missing some material and covering other material twice. Get the picture? I would imagine that someone has looked at this but I am far beyond my area of expertise at this point.

#FamousHomes #ChicagoExpensiveHomes

If you want to keep up to date on the Chicago real estate market, get an insider’s view of the seamy underbelly of the real estate industry, or you just think I’m the next Kurt Vonnegut you can Subscribe to Getting Real by Email. Please be sure to verify your email address when you receive the verification notice.